Originally published in AGS Quarterly, Association of Gravestone Studies, Volume 41, Winter 2017

By: Laura Suchan and Jennifer Weymark, Oshawa Museum

The Government of Canada has designated the period 2014-2020 as the official commemoration period of the World Wars and of the brave men and women who served and sacrificed on behalf of their country. One of the most enduring examples of war commemoration is the bronze “Dead Man’s Penny” seen on many gravestones in cemeteries across Canada. The plaques, resembling a large penny (hence their nickname), were given to families who had lost a loved one as a result of WW1.

Canada entered WW1 on August 4, 1914 when the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. At the time, Canada was a British dominion and therefore subject to foreign policy decisions made by the British parliament. During the course of the war over 619 000 Canadians enlisted and almost 60 000 lost their lives.

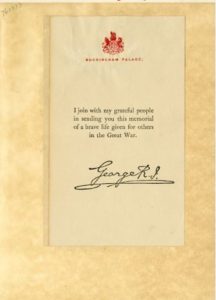

In 1916, as the Great War waged on, the British Government felt there was a need to create a memorial to be given to the families of the war dead which would acknowledge their sacrifice. A committee headed by the Secretary of the War Office, Sir Reginald Brade was created and given the task of deciding what form this memorial would take. The committee, decided on a bronze plaque officially known as the Next of Kin Memorial Plaque and a memorial scroll signed by the King.

In 1917, a competition, open to any British born person, was held to find a design for the plaque. Instructions for the competition were published in The Times newspaper on August 13, 1917 listing the stipulations for entry. For example, any design had to include a symbolic figure, meaningful to British citizens. Potential designs must also include the inscription “He died for freedom and honour” and provide space to include the name, initials and military unit of the deceased.

There were more than 800 entries submitted and Mr. Edward Preston was the successful winner. His design, a 12 centimetre disk cast in bronze gunmetal, featured the figure of

Britannia holding a laurel wreath beneath which was a rectangular tablet where the deceased individual’s name was cast into the plaque. No rank was included as it was intended to show equality in their sacrifice. The required inscription “He died for freedom and honour” was inscribed along the outer edge of the disk. In front of Britannia stands a lion and, two dolphins representing Britain’s sea power. A smaller lion is depicted biting into an eagle, the emblem of Imperial Germany. With the conclusion of the war, over 1.3 million plaques were sent to grieving families throughout the British Empire. Plaques were sent to the next of kin for all soldiers, sailors, airmen and women sailors, airmen and women serving who died as a direct consequence of their service. Plaques were also sent to the next of kin of those who died between August 4, 1914 and April 30, 1919 as a result of sickness, suicide or accidents, or as a result of wounds sustained during their time of service.

The plaques soon became popularly known as “the Dead Man’s Penny”, or “Widow’s Penny” for their resemblance to the penny coin. There was no formalized etiquette for displaying the plaques. According to Sam Richardson, assistant curator at the Ontario Regiment Museum in Oshawa, Ontario, some families chose to do very little with the plaques, the memorial scrolls and King’s messages that came with them. Often these plaques would be hidden away in drawers or chests so as not to be reminders of their loved ones. Others, however, went to great lengths to display it, with many families adding them to war memorials as they were built, or framed and mounted on walls in the family home or in a local community establishment the soldier was a part of, such as a church parish. As more time passed and military museums began to be established and grow, many descendants would also choose to donate the plaques to them.

The family of Oshawa, Ontario resident William Garrow Jr. decided a permanent home for his memorial plaque was most fitting and they chose to have it mounted into a gravestone. Garrow was born on May 15, 1894 to William and Mary Garrow., the youngest of four children and the only surviving son.

At the time he enlisted, Garrow had been working as an upholsterer and living with his parents and two sisters in the family home on Albert Street. He enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in Montreal on August 30, 1915 at the age of 21. He saw action overseas in both France and Belgium. Garrow joined up with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, the Princess Pats, as a replacement on the front lines in December 1915. He was fighting with the Princess Pats at that Battle of Mount Sorrell when he lost his life sometime between June 2–4, 1916. The family received official word of his death through a telegram. Although the final resting place of Pvt. William Garrow is unknown, he is memorialized as one of the missing on the Menin Gate in Ypres Belgium.

The Next of Kin Memorial Plaque received by William Garrow’s family remains today embedded in his tombstone in Oshawa’s Union Cemetery. It remains as a testament, over a hundred years later, to a young man’s supreme sacrifice and the depth of pride his family felt in his service to King and country.